Poets might seem like people who never say what they mean. Common rhetorical devices, like similes, complicate reality. Metaphors turn things into something they are not. Poetic language is slippery; meaning is double-edged.

In The Waste Land, it took T.S. Eliot 434 lines to set out his despair and disillusionment. “April is the cruellest month” doesn’t take much unravelling. But what to make of “A current under sea | Picked his bones in whispers”? More than a century later, scholars still debate the poem’s many meanings.

Then there are nonsense poems, which (at least on the surface) eschew sense altogether to heighten their entertainment value. And prose poetry, the confusing cousin of straight-up prose. In this context, poetry can seem like the art of not revealing you mean.

Poets are jugglers of various levels of illusion. But playing with reality does not limit poetry’s real-world impact. A poem can be a riddle and a rallying call, a puzzle and a political statement. Less literal does not mean less engaged.

So, how should writers approach the balance between substance and style? Below, I will outline four strategies for the aspiring poet-messenger: be earnest, be creative, be truthful (even when deceiving) and… give up on poetry.

What do I want to say?

For millennia, poets have played with illusion and embraced betweenness.

Poems are not quite real, not quite false; neither truth nor lie. Made up, for sure, but made up of fragments and figments and fantasies of the world or, at least, the world as the poet experiences it.

Saying one thing and meaning another is by no means the reserve solely of poets. Politicians deceive with aplomb; lawyers twist truths and mould new realities; historians re-write complex lived experiences into neat narratives. Indeed, anyone who ever speaks (or signs or writes or communicates in any way) treads a line between the literal and imagined.

But poets certainly have a reputation. Those who dabble in verse and metre have long been called liars and deceivers (as well as other more offensive terms).

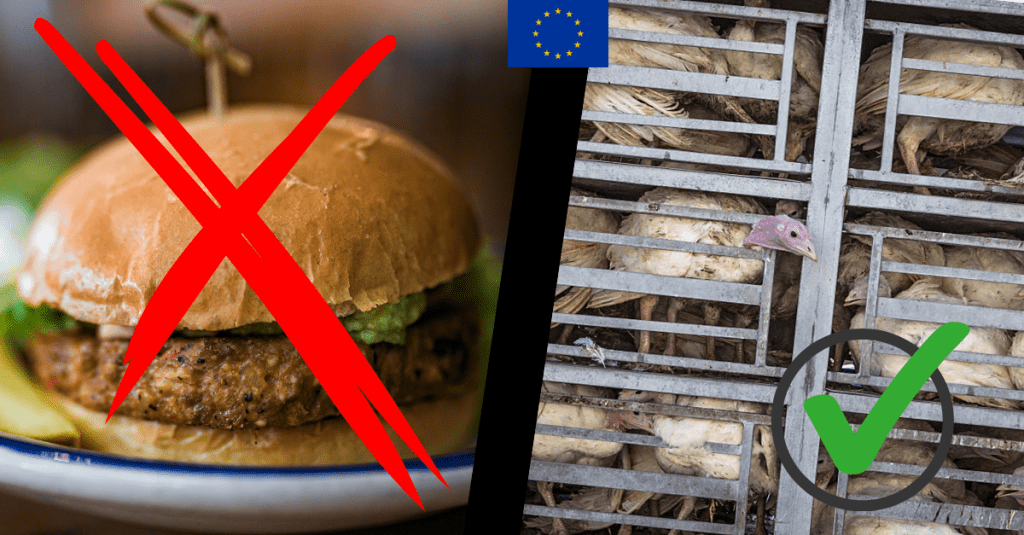

Most poets know what they want to say. That is to say, they have an IDEA. An idea can be “I want to share the story of the time I fell over in front of the whole class on the first day of Year 7 and how it made me feel”. An idea might be “the power of words” or “ants are amazing” or “capitalism corrupts”. Vegan writers might want to express through poetry the radical idea that “animals do not belong to humans”.

How do I say what I want to say?

So, perhaps more important than “What do I want to say?” is the question “How do I say what I want to say?”.

Depending on what it is you want to say, options include:

- Write a letter to your political representative;

- Create some street art;

- Join an activist group campaigning for what you believe;

- Call a friend and have a good old vent.

Another option is to write a poem.

Now, before you choose this option, you should remember: poems do not change the world. If you want to change policy (and don’t mind taking the slow road), try politics. If you want to put your passion to immediate use, consider joining or starting a campaign.

What poems can do is complement other ways of dealing with and responding to the world. (And you are, of course, free to choose more than one of the above options; or, better yet, combine them all and serenade your friend with a poem, while painting a message to your MP.)

At the risk of veering off track, it is time to talk about sense.

Making sense and sensing make

People don’t read poems in the same way they listen to public service announcements on a train station platform.

If you’re waiting in Peterborough and the tannoy cranks up, it usually means “the 15:11 to Lincoln Central has been cancelled / is delayed / has disappeared”. Passengers eager to board and reach their destination lend their ear to the announcement to learn their fate.

Poetry readers, even (or especially) those who afford great reverence to the art form, do not expect literal answers when they open a poetry book.

But they do expect to move from point A to point B, whether this is from hate to love, from ignorance to a small degree of knowledge, or from Peterborough to Lincoln.

In poetry, sense exists on a sliding scale, a scale which is different for different readers. Like a train journey – filled as they often are with crying infants, extremely loud phone calls, bad smells, good views, good company and bad company – a lot can happen between A and B in a poem. The journey may be the same but each passenger will experience it differently.

Some poems deliberately hide sense; some wear their sense on their (book) sleeve. Unravelling a poem’s many layers may shine light on its meaning. Or it might reveal a new riddle.

The rules of the game

All that to say: trying to say something meaningful in a poem involves playing a game with an invisible reader.

The rules are:

- You need to convey the IDEA to your reader;

- You need to do so in a way that at least vaguely resembles a poem.

Simple, right?

Thankfully, there are many ways to write poetry that conveys a message AND resembles a poem.

Strategies for writing meaningful poetry

Here are four strategies for writing poetry that conveys what you really want to say.

1 – Be earnest

The best poetry is often the quietest.

If your IDEA is a world-changing vision, it is possible that it is too big for a single poem (unless you are writing The Odyssey, Part II).

This is because you are likely to slip into generalisations. Poetry (like most storytelling) is more powerful when it zooms in than when it pans out. Rather than high-level concepts (“humans are selfish”, “the world is messed up”), it can be easier for readers to engage emotionally with individual stories.

This is also true in activism. Earthling Ed weaves personal anecdotes into his speeches about veganism not out of vanity but because, for his audience of pre-vegans, listening to someone’s personal journey from meat fanatic to animal rights campaigner is more persuasive and practical than hearing generalised claims about veganism.

So, the first way to write poetry that persuades is to present your message or vision in a manner that acknowledges your own limitations.

This is very different to being deferential or self-doubting. You do not need to end each poem with “this is just my opinion and you are welcome to disagree”. Nor should you compromise on your morals or water down your message to appease your readers.

But a poem that describes the sounds you heard on your first visit to a slaughterhouse, a description that makes the pain and the fear in the victims’ cries for help real to the reader, is likely to resonate more than a poem that tells them directly to stop eating animals.

2 – Be creative

Half the battle with writing meaningful poetry is resisting the urge to over-explain.

After writing a moving elegy for the farmed animals brutally forced to their deaths, it can tempting to add, as a a concluding refrain, “… and that’s why we should stop killing animals for food”.

Don’t.

People hate being told what to do. People are fed of being told what to do by governments, by advertisers, by blog writers. They do not want to be told what to do by a poem.

In the game of poetic hide and seek, there is a fine line between revealing enough to make your message clear and telling the reader what to do.

Trust that your poem is doing the job for you. If you’re not sure, ask a friend! Get five people (preferably with different worldviews and politics) to read your poem and guess what they think it is about. If none of them are even close, your message is too obscure. If two of them never speak to you again, it might be too blunt.

An earnest message creatively parcelled up in well-crafted poetic garb can communicate more meaningfully than a direct command.

3 – Be truthful (even when deceiving)

As anyone who has ever been in a theatre knows, there are layers of truth.

Watching a play involves buying into the artifice that the actor dressed in that funny hat is someone else for two hours. If you don’t embrace this, you will be sitting there thinking “why is that woman in the funny hat pretending she is someone else?”. If you over-embrace it, you’ll be angry at the end when she removes the hat, bows and exits stage left and you realise you’ve been tricked.

Poetry also plays with reality, whether shaping it into something recognisable or distorting, re-inventing or rejecting it. A poem can offer a glimpse of a better world or a new perspective on the present one. It can shine light on a truth that normally lurks in the shadows. It can magnify the miniscule that people dare not speak, or shrink a billion-dollar industry down to size so that readers can examine it more closely.

It can be easy to get caught up in your own deceit and drop a simile you haven’t really thought through (but thought sounded good) like a see-saw in a mausoleum.

You don’t need to be able to say exactly what every word is contributing. If your poetic intuition tells you that a burning image you have in mind works to convey your message and you can’t quite put your finger on why it does, you should trust yourself.

But remember: through all the creativity, all the layers of artifice, your message must shine through.

4 – Give up on poetry

This (deceptive) heading conveys a harsh but important truth: it’s time to give up on “poetry”; that’s to say, your vague notion of what a poem “should be”.

If you asked 100 people in the UK to recite a poem, you would likely hear a fair few limericks. You would also hear other form poems, such as sonnets, odes and haiku. Many would choose poems about love and death and beauty. Most would rhyme.

Forms, along with style, genre, topoi, motifs, etc., are a helpful way to think about poetry. They help catalogue and challenge ideas around poetic trends or movements and provide a framework or tradition within which new poets can situate their own writing.

But poetry is diverse. And it doesn’t “have to” rhyme.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: POETRY DOES NOT NEED TO RHYME

To get a feel for contemporary poetry, read something like bath magg. Notice how the poets innovate; how they step outside convention; how they use words as they please, not as someone else has told them words should be used.

If you choose to write in a particular form, that’s great. Make sure you understand why you are doing this and that you have some idea of the form’s history and various cultural meanings.

But don’t just write in a style you think is “poetic” because someone once told you “poems need to be like this”.

How to write impactful poetry

The first rule of impactful poetry club is that every reader is different, is impacted in different ways and by different things, has different lived experiences and different reading comprehension skills, and has different interests, habits and attention spans, so there can be no one-size-fits-all approach to writing impactful poetry.

The second rule of impactful poetry club is that combining earnestness, creativity and truthfulness (even when deceiving), while letting go of misguided pretensions of what poetry should be, is certain to result in you writing something authentic and meaningful.

And if you create something authentic and meaningful, there is a good chance that it will have some impact on your reader. ★

Vegan Poetry is a new movement of writers and readers dedicated to using our voices to advance animal rights. If you would like to join the community on WhatsApp, you can do so here: Vegan Poetry Community

Read next:

Leave a comment